http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=moEoCsCtnUc

This is my first attempt at making a short.

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Thursday, September 29, 2011

THE BIRTH OF STONE MOUNTAIN: A Geological Biography

The story of Stone Mountain’s origin is just as any

birth, just as any beginning: the story starts before conception. In the same

manner as biology is used to explain reproduction of living things, geology is

used to explain the formation of mountains. The familiarity of plate tectonics

helps create a stage on which this story will unfold. Plate tectonics, which is

a new theory that is widely accepted yet debated on its smaller details among

geologists, basically states that the Earth’s surface consists of several

different plates that are consistently moving at the rate of a few centimeters

per year. Literally, “all the world’s a stage” where Stone Mountain makes its

début and remains a present-day legend.

Once upon a time, about 300 million years ago, while

all the continents were shifting toward each other to form one supercontinent

called Pangaea, there was a landmass named Laurentia on a collision path with a

much bigger landmass named Gondwana. Because they were traveling as slow as a

fingernail grows, their seemingly gradual encounter actually ended up as a

violent crash with dramatic changes to the Earth’s surface. The two advancing

continents shattered the ocean’s crust and dislodged the smaller bodies of land

located in between. Gondwana with its powerful, gigantic structure uplifted and

thrust the fragmented ocean’s crust and the small bodies of land into

Laurentia. Because the crust and the firmer, cooler part of the outer mantle,

which are referred together as the lithosphere, are floating on top of a

mushier, extremely hotter part of the outer mantle, which is referred to as the

asthenosphere, the pile-up was steadily intensified resulting in the buckling,

folding, and wielding of the two landmasses. The Alleghenian orogeny is what

the geologists call this monstrous mountain formation that gave the final rise

to the Appalachian Mountain chain’s lower, much longer section. Yet underneath,

more upheaval arose.

Because of the newly, exceedingly thickened crust,

there were additional tremendous pressure and extreme heat that caused the

rocks within the crust to partial melt forming many pools of magma. In Mother

Earth’s womb, Stone Mountain was implanted about 8 miles deep as one of these

huge pools of magma. This egg-shaped pool of magma was incubated by the complex

dynamics of extreme force and temperature including the subduction of the

oceanic crust, which occurred when the ocean between the two shifting

continents was swallowed and shoved underneath. In just a few million years or

so, the magma cooled, solidified, crystallized, and eventually evolved into a

huge igneous rock, or even more precisely a huge granite rock. By the late

Triassic period, 200 million years ago, the continents started to drift apart

awfully slowly that during the Jurassic period, the dinosaurs and other species

roamed the partially connected continents. By the end of the Cretaceous period,

roughly 65 million years ago, the buried Stone Mountain was left behind in the

continent that will become the modern day North America, and the other

continent will become the modern day Africa.

As the periods in the Cenozoic era started to creep

by, Stone Mountain nested protectively below as a pluton, which is a geological

term for a body of intrusive igneous rock that is usually huge in size and not

tabular. This particular type of igneous rock is classified as granite that is

mostly made up of quartz, feldspar, and mica. Meanwhile above, Mother Nature’s

powerful forces were busy at work eroding, wearing down, and reshaping the

Earth’s surface. Due to this persistent process of erosion, Stone Mountain shyly,

yet boldly peeped over the worn down land. Weathering kept on breaking up and

pushing away the surrounding soil. Around 10 million years ago, the forces of

nature had unearthed over 200 feet of the seemingly growing, young Stone

Mountain. Despite that some of the minerals—especially quartz—giving the

granite its steel-like hardness, Stone Mountain is vulnerable to nature’s

elements. The dome shape is enriched by these weathering elements exfoliating

the exterior layer by layer, sheet by sheet: hence the geological term,

exfoliation sheeting. Just a million year ago, in the Quaternary period, Stone

Mountain became a unique monadnock, which is a geological term for an isolated

mountain, permanently rooted in the Piedmont region of Georgia.

Today, over 800 feet of Stone Mountain (7.5 billion

cubic feet, 1.3 miles long, and 0.6 miles wide, and coverage of 583 acres) is

exposed, yet underneath much more is left for millions of years to come. This

gigantic granite rock’s birth may be similar to other births such as the nearby

Panola Mountain, but it flourished into an appealing, distinctive, well-rounded

individual. Evidence like ancient artifacts, granite quarry, memorial carving,

numerous man-made recreational structures like the sky-ride, and worn footpaths

attests to humans’ attraction and growing presence at Stone Mountain. On one

hand, the increased flocking of humankind over the years adds to the

environmental destruction, and on the other hand countless people such as

geologists, historians, environmentalists, nature-lovers, and so forth work

hard to protect and preserve Stone Mountain. To this day, Stone Mountain bares

noticeable scars and other features depicting its life history.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Sizing Up Gattaca’s Designer Genes: Exploring Genoism through Heterosexism, Sexism, and Ableism.

By

Paula Drammeh-Davis

English 1102 Honors

Dr. Rosemary Cox

December 7, 2009

New discoveries and advancements in genetic engineering are

springing up at an alarming speed. Not only many people are concerned with the

long-term effects of existing developments such as genetic modified foods and

synthetic human insulin but also are worried about the impact that future

breakthroughs in genetic engineering might have on humanity. The film Gattaca

envisions a world where human genetic engineering is a reality and heightens

the audience’s anxiety with the appearance of the words—“The not-too-distance

future.” Gattaca is a 1997 biopunk1 science fiction film

written and directed by Andrew Niccol and starring Ethan Hawke, Uma Thurman,

and Jude Law.

The “unnaturalness” of genetic

engineering is reflected in Gattaca’s man-made, monochrome, sterile

environment. The background of the film is filled with people dressed uniformly

and moving in a steady, even pace among the vast, cold structures made of

metal, stone, and glass. Gattaca’s genetic technology generates a new

form of discrimination. The film’s hero, Vincent explains: “I belong to a new

underclass, no longer determined by social status or the color of your skin. We

now have discrimination down to a science.” Vincent also informs the audience:

“Of course, it's illegal to discriminate, 'genoism' it's called. But no one

takes the law seriously.” Despite all the laws against discrimination in

contemporary society, discrimination is still practiced because it is

institutionalized2 in society. In David A. Kirby’s article, he

refers to Antonio Gramsci’s “common sense” mentality to explain the purpose of

institutionalized discrimination. In order for the ruling class to uphold its

predominant position, it has to convince society that the ruling class’s

position is “the natural order of things” (Kirby “Extrapolating” 186). In other

words, discrimination functions to regulate people’s positions in society.

Discrimination is society’s essential character—its nature. The film uses

genoism to represent the complex discriminating nature of society. By using a

futuristic unnatural world, Gattaca exposes modern society’s complex

nature through heterosexism, sexism, and ableism3.

Heterosexism can be seen in genoism.

On his website, Gregory M. Herek, Ph.D., an internationally leading authority

on sexual prejudice, defines heterosexism as “a term analogous to sexism and

racism, describing an ideological system that denies, denigrates, and

stigmatizes any nonheterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship, or

community.” Homophobia is a term often used to describe discrimination against

homosexuality, but Herek explains the difference between homophobia and

heterosexism. Homophobia is normally used to describe individuals with antigay

views and actions, and heterosexism refers to institutionalized oppression of

people that participate in non-heterosexual activities. Some common examples of

heterosexism are when one just simply assumes a person is heterosexual and when

one believes that heterosexuality is the “natural way of things.” Heterosexism

exists in both Gattaca’s and modern society.

Gattaca hints at homosexual

and homoerotic concepts throughout the film. In their article, Laura Briggs and

Jodi I. Kelber-Kaye point out two suggestive homosexual relationships. The

first one is the relationship between Dr. Lamar and Vincent. In the scene when

Vincent gives a urine sample, Dr. Lamar refers to Vincent’s penis as “a

beautiful piece of equipment.” Indirect homoerotic implications become clearer

later in their conversation. After Dr. Lamar removes his latex gloves, which

symbolizes shifting from a clinical to a personal setting, he states: “So,

about to go up. One week left. Please tell me you’re the least bit excited”

(emphasis added). The authors interpret this statement as Dr. Lamar begging

Vincent to show him some excitement in exchange for keeping Vincent’s

secret identity (108).

Briggs and Kelber-Kaye’s second

suggestive homosexual relationship is between Vincent and Jerome (108). Jay

Clayton also discusses this relationship in his book. He states: “Jerome’s

decadent world-weariness, his aristocratic manners, his incessant affected

smoking, and his supercilious tone all contribute to the period flavor, invoking

stereotypes of the homosexual culture of Berlin between the Wars” (187-88)4.

Both of these sources find that Vincent and Jerome live together, celebrate,

and quarrel in a similar fashion to married couples (Briggs and Kelber-Kaye

108; and Clayton 188). Clayton goes further by claiming that the scene when

Jerome kisses Irene represents the consummating of Vincent and Jerome’s bond

because the kiss is an exchange of a shared woman and is witnessed by Vincent’s

rival brother (188).

Although these homosexual concepts

do not come across as homophobic, the way Gattaca uses homosexuality to

stress the “unnaturalness” of genetically enhanced reproduction is a form of

heterosexism. Briggs and Kelber-Kaye reinforce this concept by claiming that

the film pits homosexuality, characterized by unnatural, masculine, scientific

reproduction, against natural, feminine, maternal reproduction. They claim that

the film warns that when genetic technology becomes the norm and proper

maternity is absent, it will lead to a “societal decay” (94). Because Gattaca’s

“god-children” are considered weak and vulnerable, Vincent’s mother overly

coddles him. The authors find that Vincent’s “gayness” (106) is the consequence

of his mother’s excess coddling (94-95). Science is commonly associated with

masculinity and logic, and faith is commonly associated with femininity and

emotion. Therefore, the homosexuality in the film emphasizes the manly,

logical, and scientific aspects of genetic reproduction technology. By using homosexuality in this manner, the

film is indirectly reflecting modern society’s institutionalized heterosexism.

An article on the Gay, Lesbian,

and Straight Educational Network (GLSEN) website shows how

institutionalized heterosexism can be found in every level of society:

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

policy, for example, excludes all gay men who have “engaged in any homosexual

behavior since 1997” from giving blood and the community instinctively assumes

that such guidelines are in our best interest. Religious doctrine instructs

followers to “love the sinner, but hate the sin” and flocks of parishioners

unquestioningly accept that homosexuality is inherently depraved. Pentagon

policy assures us that not asking or telling is the best way to deal with our

LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender] service members and the public

takes for granted that silence is golden (while cases of anti-LGBT harassment

in the armed services rose 23% to 1,075 documented incidents in 2001). (“From

Denial”)

Heterosexism is different from the other “ism” prejudices.

Unlike racism and sexism, sexual minorities can choose to reveal or hide their

identities. According to Shaun Pichler’s online article, the ability to conceal

one’s invisible stigma5 may seem like an advantage, yet repressing one’s

true identity is “extremely challenging—and stressful.” “Coming out of the

closet” is hardly an all or nothing concept, and most sexual minorities hide

their identities when they fear damaging reactions from others (Pichler). In

other words, a person who is “outted” in his personal life but “closeted” in

his professional life faces a different set of conflicts than what a black

person or a female would face. There is a reference to this invisible stigma of

modern society in Gattaca. When Jerome asked Vincent what the surface of

Titan is like, Vincent blows cigarette smoke into his wine glass in a subtly

seductive manner and says, “Clouds around it so thick no one can tell what’s

underneath.”

Sexism can

be seen in genoism. According to most dictionaries, sexism is simply defined as

discrimination based on gender, mostly against women (“Sexism,” Free Dictionary6).

Because sexism typically affects women, the term “feminism” is sometimes used

interchangeably. By using the sociological definitions of these terms, the

diverse political and personal perspectives of these terms can be excluded. The

sociological perception of sexism includes stereotyping based on gender and

favoritism toward the gender with power (“Sexism,” Online Dictionary), and the

sociological perception of feminism refers to various political and

intellectual movements that seek to change women’s positions in society

(“Feminism”). Although these terms are

closely related, the term “sexism” does not assume that only women are

oppressed and functions more as an umbrella to include discrimination against

both genders. Sexism exists in both Gattaca’s society and modern

society.

Sexism is

echoed throughout the film. Future improvements in reproductive technology

would be expected to be in women’s favor, but that is not the case in Gattaca. In her article, Susan A. George’s observation on the scene of

Vincent’s birth is that the childbirth process in Gattaca remains the

same as today. George finds that the goal of Gattaca’s advanced reproductive

technology is not to make it safer or easier for women during the birthing

process—“but to improve the product” (178). The product is the genetically

enhanced offspring. Women’s primary purpose is to act as “mere incubators”

(177).

George also

observes that the film has the same sexist stereotypical jobs as modern

society. For example, two delivery nurses, a teacher, and a restaurant hostess

are played by females, and the doctor who delivers Vincent, the geneticist who

enhances Vincent’s brother’s DNA, and the majority of the workers at Gattaca,

the fictional company resembling NASA, are played by males. Therefore, the film

projects “a man’s world” controlling the reproduction process (178-79).

Gattaca

does address sexism by applying the “glass ceiling”7 scenario to its

hero. While Vincent is working on the cleaning crew at Gattaca, he is literally

gazing through the glass structures that he is cleaning—gazing at the employees

that have his dream job. George, as well, mentions that the film applies the glass

ceiling to the in-valids (179). When Vincent applies for his dream job with

Jerome’s genetically enhanced DNA, the interviewer just looks at the DNA

profile assuming that it provides all the information he needs to know.

Vincent’s voiceover makes it evident: “My real résumé was in my cells.” Vincent

is not able to break through this invisible barrier without using Jerome’s DNA

profile.

Despite

feminists’ progress, modern society’s glass ceiling is still holding strong. In

her article, Hannah Clark points out that a 2006 survey of 1,200 executives in

eight countries (including U.S., Australia, Austria, and the Philippines) by

Accenture, a prominent, global consulting firm, found that about seventy

percent of women and fifty-seven percent of men believe that a glass ceiling

does exist. She brings up an interesting point:

“But if women are unhappy about

making 77 cents for every dollar earned by a man, it is not reflected in

Accenture’s statistics. Globally, the same percentage of men and

women—58%--felt they were fairly compensated. In the U.S., 67% of men were

happy with their salaries, compared with 60% of women. But American women were

almost as satisfied as men with the professional levels they had achieved.”

(Clark)

Clark’s article may provide some answers to why the glass

ceiling still exists. She asks several different experts, “Are women happy

under the glass ceiling?” The following examples are some of the responses. In

his book, Why Men Earn More, Warren Farrell states that women tend to

place a higher priority on their families than their jobs. A study by the

Center for Work-Life Policy, “The Hidden Brain Drain: Off-Ramps and On-Ramps in

Women’s Careers,” suggests that even ambitious women tend to measure success

more with their relationship with colleagues and their involvement within their

communities as opposed to men’s measurement of success with salaries and job

titles. Susan Solovic, CEO of sbTV.com [Small Business Television], refers to

the statistics from the Center for Women’s Business Research that show between

1997 and 2004, the number of women-owned firms increased seventeen percent

while the total number of firms only grew nine percent to make her point:

“There is really no glass ceiling when it comes to owning your own business”

(qtd. in Clark). Because sexism is embedded so well in modern society, women

often unintentionally contribute to sexism.

A unique

example that shows how deeply sexism is institutionalized in modern society is

revealed in the experiences of male to female transgenders8. In her

essay, Judith A. Howard notes that several transsexuals discover sexism after

their male to female transition. For example, in 1996 the Chronicle of

Higher Education reported the sex change of Donald McCloskey, a

distinguished male economist at the University of Iowa. This article focuses on

how his authority and the influence of his work were affected by his transition

(Howard 550). One colleague commented, “Some people’s reaction is that this is

a real shame because we are going to lose a strong male voice standing up for

female economists” (qtd. in Howard 550).

On one hand, this statement expresses the desire to have more

influential men with feminist views, and on the other hand, this statement is

echoing sexism by expressing that a “strong male voice” is needed to defend

females. Another quote by a journal editor reflects sexism: “Those who

disagreed with Donald’s criticisms of the field may now discount what Deirdre

[McCloskey’s female name] has to say…” (qtd. in Howard 550). There is a

reference to modern society’s unintended acceptance of sexism in Gattaca.

When Irene catches Vincent watching the rocket ships shooting upward into space

through the skylight, she tells him, “If you’re going to pretend like you don’t

care, don’t look up.”

Ableism can be seen in genoism. In

his blog, Tim Moore defines ableism as discrimination against disabled people,

which includes the preference and favoritism toward people without

disabilities, the perspective that disability is not normal or acceptable, and

the act of excluding and preventing the disabled from participating in common

activities. The term “ableism” was coined in the early 1980’s as disability

rights became a frequently discussed topic in politics. Moore clarifies that

disableism has the same meaning as ableism because the word “disabled” seems

more appropriate to describe discrimination against those who have

disabilities; hence, some people choose to use the term “disableism” instead.

Disableism is the preferred term in the United Kingdom. Ableism exists in both Gattaca’s

society and modern society.

In Gattaca, those who are

not genetically enhanced are considered and treated as disabled, and they are

called degrading terms such as “in-valids” and “degenerate” (pronounced

with a long “e”). The following are examples of how the ableist aspect of

genoism becomes institutionalized into Gattaca’s society. After

Vincent’s birth, the nurse reads aloud his genetic readout that predicts his

death at the age of thirty from a cardiac disorder. Later on, Vincent is denied

entry into school because the school’s insurance will not cover “god children.”

Because of these hardships, Vincent’s parents are pressured into using genetic

enhancements for their second child. In the film, the norms are changed so that

conceiving a child “naturally” is considered old-fashioned and genetic

engineering is considered the new “natural” way to procreate; therefore,

Vincent’s parents are pressured by society into conforming to these norms.

Vincent is only able to obtain a high-ranking job with Jerome’s DNA. When Irene

develops a romantic interest in Vincent, she privately pays for a genetic

readout on a strand of hair that was found at Vincent’s workstation. The

genetic readout makes a good impression, because it belongs to the genetically

enhanced Jerome. These scenes show how genetic technology impacts one’s social

class status in a similar fashion as birthright and financial situation impact

one’s social class status in modern society.

According to Rene Harrison’s blog,

the audience tends to overlook the fact that they too would be considered

disabled in Gattaca’s futuristic society. To explain one reason for this oversight, Harrison uses Mitchell

and Snyder’s narrative prosthesis concept.9 Harrison notes that

Vincent’s disabilities includes having a visual impairment, having a weak

heart, and being a “god child;” Jerome’s disabilities includes being

wheelchair-bound and lacking the spirit that Vincent has. Together Jerome and

Vincent represent the normative ideal. Referring to the narrative prosthesis

concept, Harrison explains that Jerome’s purpose is to serve as a support for

Vincent’s disability in the same manner as a prosthesis supports by

inconspicuously concealing the dependencies of the disability. In other words,

this narrative prosthesis makes it easy for the audience to not notice Vincent

and Jerome’s disabilities.

Harrison

also points out that that Vincent tends to be seen as “the everyman figure”

overcoming his obstacles and achieving his goals with determination. This view

of Vincent tends to blind the audience to the fact that Vincent is dependent on

others to help him and has to cheat to accomplish his goals. She believes that

the film’s almost-missed message is that “nobody makes it alone.” With this suggestion

that those who are considered able-bodied are just as dependent on others for

help as those who are considered disabled, the conflicting viewpoints toward

disability and advanced technology can be understood. On one hand, there is the

advantage of the assistance that the technology provides. On the other hand,

there is the disadvantage of being labeled negatively as dependent and disabled

by society.

Modern society’s ableism appears in

ethics discussions surrounding the prenatal genetic testing and selection

process. In their article, Aline K. Kalbian and Lois Shepherd maintain that the

consequences of prenatal genetic testing and selection that are often ignored

in the academic and clinical fields are addressed in the writings of the

“disability rights critique” and in pop culture narratives such as Gattaca.

Because the goals of prenatal testing and selection are assumed to be good,

most people do not question the motive of attempting to avoid genetic diseases

such as Tay-Sachs and Down’s syndrome (15). The process of avoiding inherited

disabilities is a form of ableism because there is preference and favoritism

toward the fetuses or embryos that test negatively for inherited disabilities.

The authors find that contemporary culture accepts these testing procedures as

preventive medical care by believing that the disabled person-to-be is better

off by not existing with his or her disability and by believing that the health

of society is improved without the existence of people with such genetic disabilities

(15). The authors show another viewpoint with David Wasserman’s argument that

states that this avoidance of certain inherited conditions should not be

considered medical procedure because it does not “protect or restore an

individual’s health” and that prenatal diagnosis is “typically, a procedure to

identify and destroy unwanted organisms” (qtd. in Kalbian and Shepherd 19).

They reinforce Wassermann’s points by claiming the goal should be to obtain

medical benefits—“not merely promote patient choice.” An example of patient choice is providing “testing for traits

not associated with disease or pathologies, such as testing sex selection or

(hypothetically) eye color” (Kalbian and Shepherd 19). The selection aspect of

the procedures leads to normalization, which is to conform to a certain

standard or norms.

According to Sandra J. Levi’s

article, ableist normalization is when one assumes that normal physical,

mental, and behavioral abilities are beneficial in spite of a person’s true

capabilities (2). Levi states that research shows that the belief that normal

traits are equaled to desirable traits may be harmful to the disabled: “For

example, educators and parents may assume that deaf children will better

negotiate the hearing world with oral language than with manual language (e.g.

sign language). A large body of research, however, demonstrates that deaf

children make greater educational achievements when manual, rather than verbal,

language skills are emphasized” (2). The damaging effect of this special

treatment toward those considered disabled is reflected in Gattaca.

Vincent explains that "From an early age, I came to think of myself as

others thought of me: chronically ill. Every skinned knee and runny nose was

treated as if it were life-threatening."

The

audience’s reactions to Gattaca’s original ending indicate that modern

society is not only uncomfortable with being confronted with its

institutionalized ableism but is also uncomfortable with being labeled as

disabled as individuals. The original

ending has a black background with the following messages:

In a few short years, scientists

will have completed the Human Genome Project, the mapping of all the genes that

make up a human being. We have evolved to the point where we can direct our own

evolution. Had we acquired this knowledge sooner the following people may never

have been born.

Next are pictures of people labeled with their names and

their inherited disorders:

Abraham Lincoln, Marfan Syndrome;

Emily Dickinson, Manic Depression; Vincent Van Gogh, epilepsy; Albert Einstein,

Dyslexia; John F. Kennedy, Addison’s disease; Rita Hayworth, Alzheimer’s

Disease; Ray Charles, Primary Glaucoma; Stephen Hawking, Amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis; Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Asthma.

A powerful, bleak statement follows this list: “Of course,

the other birth that may never have taken place is your own.” In his article,

Kirby explains why this ending was omitted (“New Eugenics” 209). According to

Gail Lyon, the film’s co-producer, the ending was cut after the members of the

non-scientist audience felt “personally attacked” as having genetic flaws (qtd.

in Kirby “New Eugenics” 209). If this

ending had not been cut in the theatrical releases, Harrison’s argument that

the audience tends to miss that they too are considered disabled in Gattaca’s

society would be moot.

Gattaca

illustrates society’s discriminating nature in the dark world of genoism. The

film shows the complexity of society’s discriminating nature beyond racism

through heterosexism, sexism, and ableism. Genoism includes many layers of

discrimination that are found in modern society. Gattaca is more about

showing society’s true nature than predicting society’s future. Ashley Montagu

captures this concept: “the dead hand of the past may continue to guide the

practice of the present as well of the future” (qtd. in Kirby “Extrapolating”

193).

Notes

1. Biopunk is a science fiction sub-genre that focuses

on scientific advancements in biology. The term is a spin off from the term

“cyberpunk,” which describes stories about information technology (Quinion).

2. “Institutionalized” is a verb

form for “institutionalization,” a sociological term meaning predictable social

interaction patterns within a social structure that are regulated by norms

(“Institutionalization”).

3.

Racism is obviously an aspect of genoism. Because racism is the topic in

several experts and critics’ writings, the focus will be on the discriminating

aspects of genoism that are not as noticeable.

4.

Clayton adds that these stereotypes are best known to movie fans from the 1972

film Cabaret (188).

5.

Pichler uses Goffman’s stigma theory, which “proposes that attributes about

individuals are devalued in certain social or cultural contexts and are,

therefore, stigmatized.” Using other sociological studies, he explains that

sexual orientation is referred to as an invisible stigma because it is not

readily visible.

6.

The Free Dictionary by Farlex is a website that offers

definitions from multiple dictionaries including The American Heritage

Dictionary of the English Language and Collins English Dictionary.

7.

The wiseGeek website describes the glass ceiling as a metaphor for an

invisible barrier that prevents women from climbing the corporate ladder

(Wallace).

8.

“Transsexual” refers to an individual who seeks to become the other gender. By

acknowledging an individual’s sexuality is different from an individual’s

gender, the more recent preferred term is transgender (“Transsexual”).

9.

Huff explains that narrative prosthesis is mostly used by literary

critics. This concept is also an

interest for scholars in other disciplines because one of this concept’s

central ideas is that identity is created within discourse and that in some

aspect the concept gets its influence from narratives (201).

Works Cited

Briggs,

Laura, and Jodi I. Kelber-Kaye. “‘There is No Unauthorized Breeding in Jurassic

Park’: Gender and the Uses of Genetics.” NWSA Journal 12.3 (2000):

92-113. Sociological Collection. GALILEO. Web. 1 Oct. 2009.

Clark, Hannah. “Are Women

Happy Under the Glass Ceiling?” Forbes.Com. Forbes. 3 Aug. 2006. Web. 25

Nov. 2009.

Clayton,

Jay. Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century

in Postmodern Culture. New York: Oxford UP, 2003. 185-89. Print.

“Feminism.” Online

Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Athabasca

University and ICAAP.

Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

“From Denial to Denigration:

Understanding Institutionalized Heterosexism in Our Schools.” The Gay, Lesbian

and Straight Education Network. GLSEN. 30 Apr. 2002. Web. 28 Nov.

2009.

Gattaca. Writ. and Dir. Andrew Niccol. Perf. Ethan Hawke, Uma

Thurman, and Jude Law. Columbia TriStar Home Video, 1998. DVD.

George, Susan A. “Not

Exactly ‘of Woman Born.’” Journal of Popular Film & Television 28.4

(2001): 176-83. Academic Search Complete. GALILEO. Web. 1 Oct. 2009.

Harrison, Rene.

“Revealing Disability: Gattaca and the Ideology of Ableism.” Politics

of Writing Rhetoric Blog. Just Another Word Press.Com Weblog, 18 Sept.

2009. Web. 1 Oct. 2009.

<http://politicsofwriting.wordpress.com/2009/09/18/revealing_disability_gattaca_and_the_ideology_of_ableism/>

Herek, Gregory M. “Definitions: Homophobia,

Heterosexism, and Sexual Prejudice.” Sexual Orientation: Science, Education,

and Policy. 22 May 2008. Web. 22 Nov. 2009.

Howard, Judith A.

“The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same? Reflections on the state

of Sexism.” Sociological Forum 13.3 (1998): 545-55. JSTOR.

GALILEO. Web. 25 Nov. 2009.

Huff, Joyce L.

Rev. of Disability, Human Rights and Society, by Mairian Corker and

Sally French, and Narrative Prosthesis: Disability and the Dependencies of

Discourse by David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder. NWSA Journal

14.3 (2002): 201-204. Project MUSE. GALILEO. Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

“Institutionalization.”

Online Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Athabasca University and ICAAP.

Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

Kalbian, Aline

H., and Lois Shepherd. “Narrative Portrayals Flourishing of Genes and Humans.” American

Journal of Bioethics 3.4 (2003): 15-21. Academic Search Complete.

GALILEO. Web. 1 Oct. 2009.

Kirby, David A.

“Extrapolating Race in Gattaca: Genetic Passing, Identity, and the

Science of Race.” Literature and Medicine 23.1 (2004): 184-200. ProjectMUSE.

GALILEO. Web. 1 Oct. 2009.

---. “The New

Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in Gattaca.” Science

Fiction Studies 27.2 (2000): 193-215. Film & Television Literature

Index with Full Text. GALILEO. Web 1 Oct. 2009.

Levi, Sandra J.

“Ableism.” Encyclopedia of Disability. Ed. Gary L. Albrecht. N.p.: SAGE, 2006. Web. 22 Nov. 2009.

<http://www.uk.sagepub.com/upm-data/5900_Entries_Beginning_with_A_Albrecht_Pdf.pdf>

Moore, Tim. “What

are Ableism and Disableism?” My Disability Blog. Blogger. 5 Nov.

2009. Web. 22 Nov. 2009.

Pichler, Shaun.

“Heterosexism in the Workplace.” Sloan Work and Family Research Network.

Boston College. 3 Apr. 2007. Web. 28 Nov. 2009.

Quinion, Michael.

“Biopunk.” World Wide Words. 13 Sept. 1997. Web 22 Nov. 2009.

“Sexism.” The

Free Dictionary by Farlex. Farlex. Web. 22 Nov. 2009.

“Sexism.” Online

Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Athabasca

University and ICAAP. Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

“Transsexual.” Online

Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Athabasca

University and ICAAP.

Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

Wallace, O. “What

is the Glass Ceiling?” wiseGEEK. Conjecture Corporation. Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

God Hates Polysemous Signs: Applying the Various Definitions of Cult to Westboro Baptist Church

Photo by Mike Burstein. 28 Oct. 2008. 28th Burstein!'s photostream. Flickr.Com

Paula Drammeh-Davis

Research Paper

March 24, 2011

Social Problems 1160

Although it is expected for one’s past to shape his present, one’s present shape may unexpectedly become irregular. Two years after he earned a law degree from Washburn University in 1962, he started his own law firm in Topeka, Kansas, which will later be staffed mostly by his adult children. At first, the firm gained recognition for its numerous cases that dealt with civil rights such as African American clients claiming discrimination by school systems, a predominately black American Legion alleging police abuse, non-white clients accusing discrimination by Kansas Power and Light, Southwestern Bell, and the Topeka City Attorney, two female professors claiming discrimination by universities in Kansas, and so forth. One website quoted his daughter: “We took on the Jim Crow establishment, and Kansas did not take that sitting down. They used to shoot our car windows out, screaming we were nigger lovers,” and claims that their firm represented one-third of civil-rights cases on Kansas’s federal docket (qtd. in “About”). These cases earned him three awards in 1986 and 1987; notably, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People gave one of the awards (“About”; “Timeline”).

It may be shocking to most people that the above person is the very one and same Pastor Fred Phelps from the notorious Westboro Baptist Church (WBC). By picketing various events with signs expressing extreme statements of hatred and intolerance, they are constantly making waves in the news, which is paradoxical when compared to their civil rights history. Most recently, the Supreme Court’s ruling that their offensive protests are protected by the First Amendment has been splashed all over the media. The fact that WBC considers other conservative Christian denominations, including both mainstream and fundamental ones, to be too liberal or too radical exemplifies their extreme reactionary beliefs. An example was stated on one of their now-deactivated websites: “Methodist, Episcopal, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Catholic, Northern and Southern Baptist, Church of Christ, Assembly of God, etc. have all departed from God. Most well-known preachers (Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, etc.) have departed from God, and disassociated themselves with pure Gospel preaching” (qtd. in “WBC: In Their Own Words”). Myriad critics from all walks of life have many definitions for this unorthodox flock ranging from cult to hate group, but most frequently just as “a bunch of nuts.” From a sociological perspective, is WBC a cult? By looking closer at not only how the usage of the term “cult” in an academic discipline differs from the mainstream usage but also the different usages of “cult” within the sociology field, one can see how WBC fits and does not fit the profile of a cult.

In his book, The New Believers, David V. Barrett devotes the entire second chapter to the problematic, complex definition of the word “cult.” The author’s first main point is that the definition depends on who is using the word. Journalists, theologians, preachers, psychologists, sociologists, anti-cult activists, and so on refer to the word “cult” differently because of their diverse positions and intentions (Barrett 19). Barrett compiles laypeople’s stereotypical associations with cults such as peculiar religious beliefs, unseemly practices, usage of false promises to tempt people to join, money swindling, an unscrupulous, controlling leader, brainwashing, and so forth, and he gives an example of how a tabloid journalist and an anti-cult watch group often take advantage of the above, implied, derogatory mindset toward the term “cult” as an unspoken definition because these assumptions serve their purpose—unlike a more neutral term such as “sect” or “alternative religion” (20). Other familiar usages of “cult” are mentioned in the chapter, but the author’s above point captures the subjective meanings of “cult” as opposed to the objective meanings used within the academic circle.

Studies on cults are found primarily in two interdisciplinary fields: sociology of religion and social psychology. Sociology of religion focuses on religious organizations’ roles in society, and social psychology focuses on relations between individuals and groups. Both of these fields are not concerned with the validity of a cult’s ideology. The sociology of religion’s typology provides an objective definition of cult, and the social psychology’s concentration on the relationships within a cult offers different characterizations for cults.

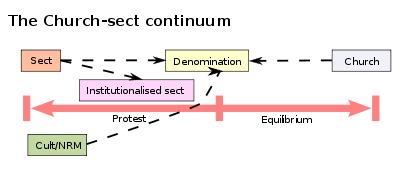

The church-sect typology is a widely used framework in sociology of religion that defines the different type of religious organizations on a continuum.

Even though the typology looks simple, it is based on ideal types, which can be a misleading term. “Ideal type” is a sociology term that has nothing to do with perfect or desirable traits. Ideal types are constructed from common, consistent elements found in typical cases. Because reality consists of variations, ideal type is mostly used as a tool to measure or compare any given sociological subject. Basically, the first type, a church exists when there are no other competing religions in its society, and it is usually entangled with its society’s politics and economics. A recognizable example is the Roman Catholic Church in 12th century Europe before religious pluralism. Denomination occurs when a church loses its monopoly such as the present day Roman Catholic Church (In some Latin American countries, it still qualifies as a church.) or when a sect’s membership grows and become more established such as Lutherans. A sect is a religious group that splits from its parent religion, which is typically a denomination. Sects usually claim that their parent denominations have become too liberal and vow to return to the “true religion.” Most denominations in the U.S. started as sects like Baptists and Seventh-day Adventist. If a sect does not dissolve or develop into a denomination, it tends to remain steady in growth and forms fixed norms or, in other words, become institutionalized. An example of an institutionalized sect is the Amish. The chief distinction between a cult and a sect is that a cult embraces new religious concepts instead of advocating the return to the “pure religion.” Cults often claim that they have discovered lost or forgotten sacred texts or a new prophecy. Other distinctions include that a cult is rarely a split from a parent religion, often combines existing religious ideologies, tends to remain in a transitory state that will later dissolve after the death of its leader or founder, and is most likely led by a charismatic leader, who bring forth the new or lost religious concept which becomes the focal aspect of the cult. For example, The Book of Mormon and temple worship are new concepts that originally defined Mormons (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) as a cult, but now most sociologists label them as a denomination due to their growth and their development of more mainstream religious characteristics (“Introduction”). The above typology and brief summary of the ideal types of religion help illustrate not only the objective, traditional identification of cults but also how it relates to other classifications of religions.

Yet still another complication exists with defining cult among scholars. The term “new religious movement” (NRM) is often used by some modern day sociologists in order to avoid the pejorative implications of the word “cult” (“Introduction”; Barrett 24). The debate surrounding the NRM is noted in several sociological texts including Barrett’s book. The problem with the NRM term is that not all NRMs are new. For example, in the East the Hare Krishna movement is best described as an ancient variant of Hinduism, but in the West, the movement (better known as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness) fits the NRM description. After Barrett gives details for other arguments over the NRM term, his conclusion, similar to that of many other sociologists, is to use Eileen Barker’s proposal that NRM is a term designated to religious movements formed after WWII and to use the term “alternative religion” for both NRMs and older religious groups (sects and cults) that are different from mainstream religions (24).

Where does WBC fit in the church-set typology? WBC refers to itself as Primitive Baptist also known as Old School Baptist (“About”), which is a sect of Baptist that is characterized mostly by its Calvinistic beliefs, especially predestination (Daniels), although no mainstream Primitive Baptist churches claim any association with WBC. Eastside Baptist Church built a new church, named it Westboro Baptist, and asked Fred Phelps to become pastor of the newly built church. WBC officially opened in May of 1956, but very soon afterwards Phelps lost support from Eastside’s congregation mostly due to his hostile behavior and preaching beliefs that went beyond Eastside’s strict conservative beliefs (Bell). Based on this above history, it is clear that WBC split from a denomination. The blurred aspect is that WBC is claiming to be a sect known as Primitive Baptist, yet Phelps preaches a more extreme version of the mainstream Primitive Baptist doctrine. By viewing WBC as putting a new spin or a different emphasis on an existing sect’s dogma, WBC can easily be seem as a cult masquerading as a sect. On the other hand, WBC claims that it is returning to the very basic concept of Primitive Baptist dogma, and this suggests a newly formed sect splitting instantly off a parental sect. Since one main trait of a cult is adding a new concept to an existing religious concept, WBC’s belief on how “true Christians” should behave, express their viewpoints and treat nonmembers (referring mostly to their numerous protests and lawsuits) is a vastly new behavior for religious organizations in a developed country. This aspect of WBC makes WBC more of a cult than a sect.

In the social psychology field, the term “cult” has very little to do with classification of religion organizations, and much more with group dynamics. In his book, Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies, Arthur Goldwag offers a clear interpretation of the word “cult” that is used among cult experts: “…a coercive or totalizing relationship between a dominating leader and his or her unhealthily dependent followers… how much authority its leaders grant themselves—and how slavishly devoted to them its followers are” (4). Goldwag points out that Wicca, Gnosticism and many other religious movements, which fit the description of alternative religions, often lack the controlling and abusive characteristics. Thus they are not viewed as cults (5). Cult scholars in this field are often associated with secular or human rights anti-cult movements instead of the religious-based cult watch groups like the Apologetic Index website. Since cult is defined solely on the configuration of an organization, non-religious groups can also be considered cults. Some of Goldwag’s examples include Taliesin (Frank Lloyd Wright’s School of Architecture), Hitler’s Nuremberg rallies, and Amway (a multilevel marketing company) (7).

Anti-cult advocates may use the word “brainwashing,” but experts in cultic studies avoid using this popular term. “Brainwashing” was originally coined by a journalist, who poorly paraphrased a scientific research, and the controversial “brainwashing theory” used in many court cases will later become a hypothesis discredited by the American Psychological Association (Barrett 30). A renowned psychologist, Robert Lifton’s studies, especially his study on American prisoners after the Korean War, are commonly mentioned by numerous experts; however, it was his research that was unfairly blemished by the word “brainwashing” (Barrett 30). Nevertheless, many professionals including both Barrett and Goldwag still refer to Lifton’s research (Barrett 30; Goldwag 5); moreover, the usage of the term “brainwashing” can be an indication of the author’s credibility. According to many of his writings, Lifton is convinced that there is a global epidemic of ideological totalism, which is threatening civil liberties. Cult is one form of ideological totalism that Lifton addresses in his article, “Cult Formation[1].” In this article, Lifton states that there are three recurring psychological themes in cultic studies that can be used to identify a cult: “1) a charismatic leader who increasingly becomes an object of worship as the general principles that may have originally sustained the group lose their power; 2) a process I [Lifton] call coercive persuasion or thought reform; 3) economic, sexual, and other exploitation of group members by the leader and the ruling coterie.” The article continues by explaining methods of ideological totalism that are very much the same as the eight criteria for thought reform outlined in his book, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, which is posted on several websites.

Of Lifton’s three identifying traits for a cult, WBC fits the second one on thought reform and the third one on exploitation the best. The first one referring to a charismatic leader is iffy. Fred Phelps is hardly described as charming in the media, but in his youth there are a few accounts that suggest he can be somewhat appealing. In 1951 when Phelps was 21 and attending John Muir College in Pasadena, California, (before WBC’s existence), he was featured in Time Magazine as a soapbox preacher: “…drew crowds of up to 100. Over & over he denounced the ‘sins committed on campus by students and teachers…promiscuous petting…evil language…profanity…cheating…teachers’ filthy jokes in classrooms…pandering to the lusts of the flesh’” (qtd. in “Religion”). When Fred Phelps first arrived at Eastside Baptist Church, he was so well liked that the congregation hired him as an associate pastor (Bell). By reading various narratives about Phelps’ background, the general impression is that when people disagree with or confront Phelps he will react in a hostile manner. Phelps’s hostility isolates him from people whereas a typical cult leader uses his charisma to smooth people over.

By applying Lifton’s criteria on thought reform and exploitation to WBC one can show how “cultish” the flock is. The WBC flock has been cited to have between 71 to 150 members by various sources. A majority of the members, about 90 of them, are related by blood or marriage. Basically the Phelps clan is three generations that include the nine loyal adult children and their children (“About”). The fact that WBC is mostly just one family clan emphasizes Phelps’s tendency to isolate himself and family from the rest of the world, and the reason there are often children involved in the protest events is that the children are his grandchildren. Fred Phelps has 13 adult children, but four of them are estranged. His seventh child, Nate Phelps is now speaking out about his abusive childhood. He has an official website, gives numerous speeches against the dangers of religion and child abuse, advocates for LGBT, and is currently writing a book about his childhood (Phelps). Most of the inside story of WBC’s early days, which are often used in other sites, comes from Nate Phelps’s interviews, speeches, and blogs. Bell’s online narrative, Addicted to Hate: The Fred Phelps Story, mostly quotes both Nate and Mark Phelps, the second son who is also estranged, when describing what it was like to grow up in the Phelps household.

Lifton’s two main criteria for thought reform are “Milieu Control” that refers to “the control of all communication within a given environment” and “Mystical Manipulation” that is the choreography of experiences that appear spontaneous but are planned. Fred Phelps purchased adjoining houses around his original house/church creating a compound that shares a common backyard (Bell). This geographical isolation is one way to control communication with the outside society. Although Nate and Mark both attended public school, they were not allowed to attend classes that taught evolution and Christmas events. Their father threatened to sue the school; therefore, Nate and Mark often sat in the library during these occasions (Bell). Lifton’s examples of mystical manipulation techniques include fasting, chanting, and limited sleep. Mark Phelps’s bio page states that he “…was taught his father’s extreme version of Calvinism from an early age. This was accompanied by extreme physical punishments and abuse, extreme dietary and health requirements, and other extreme expectations.” Another Lifton’s criterion is “Demand for Purity” that is when members are constantly pressured into conforming to the viewpoint of the world as black and white and into striving to fit the ideal. WBC’s messages during protests and other public appearances obviously illustrate not only the above criterion but also another Lifton’s criterion, “Dispensing of existence.” Dispensing of existence refers to the privilege to decide who has the right to exist or not. WBC’s belief of predestination and never-ending assertion that all outsiders are sinners and are “going to burn in hell” exemplifies this. The above is just a very brief summary of comparing some of Lifton’s criteria to WBC; moreover, this shows the strong aspect of WBC as a cult without going into in-depth details of the family’s history.

What makes WBC dramatically not a typical cult is that it is not making any effort to grow with new members. WBC purposefully isolates itself from society at large by staging protests that offend almost everyone. Despite their strange dogma and behaviors that gives a distinct impression that they are insane, WBC consists of well-educated, skillful lawyers who are constantly filing frivolous lawsuits often associated with the First Amendment despite their hatred toward America. WBC has been awarded million of dollars in various lawsuits (“About”; Bell). Some critics claim that WBC is just a fake religious organization using their infamous protests for monetary gains, but Fred Phelps’s past strongly suggests that he genuinely has zealous, radical beliefs. There is clearly some truth behind the concept that WBC puts itself out there publicly in an unfavorable way anticipating their civil rights to be violated for financially gain. Although it is sometimes common for cults to desire media attention, WBC’s method of economical support is atypical for cults.

Another way that WBC is stunting its growth is that Fred Phelps forbids marriage outside the church, and Phelps’s granddaughters expressed no desire to marry because they claim they are “…living in the last of the last days” in a documentary entitled, The Most Hated Family in America (qtd in “About”). Sociologists in religion do characterize cults as having a tendency to remain in transitory state. If the cult does not grow and become a more established religion, it will dissolve after the death of its founder or leader. A historical example of a cult’s birth and growth is Christianity. Before his death, Jesus and his followers would be described as a Jewish sect as well as the period after his death when his brother James led the Jerusalem church. When Paul became the leader with a different focus, the reformist Jewish sect became the cult of Christ. Christianity did not become a major religion until Emperor Constantine legalized Christian worship (Barrett 21). Now that Fred Phelps is advancing in age, what is WBC’s future? Will the group dissolve? It doesn’t seem likely because these last few years Phelps’s daughter, Shirley Phelps-Roper, who is an attorney at the Phelps Chartered Law Firm, has been the running the daily operations and acting as the spokesperson for WBC (“About”; Bell). She may be changing the WBC’s focus. Recently many critics have been describing the group more as a religious hate group similar to the Ku Klux Klan. Personally, I consider WBC to be a cult—just a new type of cult that uses modern technology and laws in order to fight against modern society’s more liberal values. Most of all, I hope that the Phelps clan overlooks the biblical story of Lot’s daughters in Genesis 19: 30-38 when seeking growth for the church. Works Cited

“About Fred Phelps.” God Hates Fred Phelps. WordPress.Org.WordPress, n.p. Web. 10 Mar. 2011.

Barrett, David V. The New Believers: A Survey of Sects, Cults, and Alternative Religions. London: Cassell, 2001. Print.

Bell, Jon Michael. Addicted to Hate: The Fred Phelps Story. The Anti-Phelps Underground, n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2011.

Daniels, W.R., Jr. “Predestination.” Primitive Baptist Online. PrimitiveBaptist.org, n.p. Web. 20 Mar. 2011.

“Fred Phelps Timelime.” splcenter.org. Southern Poverty Law Center, 2011. Web. 10 Mar. 2011.

Goldwag, Arthur. Cults, Conspiracies, and Secret Societies. New York: Vintage, 2009. Print.

“Introduction to Sociology/Religion.” Wikibooks: The Open-Content Textbooks Collection. Updated 25 Feb. 2011.The Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 8 Mar. 2011.

Lifton, Robert Jay, M.D. “Cult Formation.” Cultic Studies Journal 8.1 (1991): 1-6. International Cultic Studies Association. ICSA Inc., 2011. Web. 15 Mar. 2011.

Phelps, Nate. Nate Phelps Official Website. Natephelps.com, n.d. Web. 20 Mar. 2011.

“Religion: Repentance In Pasadena.” TIME in partnership with CNN, 11 Jun 1951. TIME Inc., 2011. Web. 20 Mar. 2011.

“Westboro Baptist Church: In Their Own Words: On Christians.” Extremism in America. ADL. The Anti-Defamation League, 2011. Web. 20 Mar. 2011.

[1] This article is an electronic reprint with no indication of the printed version’s page numbers despite the pagination in Works Cited.

Popping my blog cherry.

I hope this will not be too painful. I hope this will not end in a bloody grammar mess. In a drunken haze, I attempt to translate the demonic visions into written language. Oh the fright, the abuse. No one is safe. Will I ever climax?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)